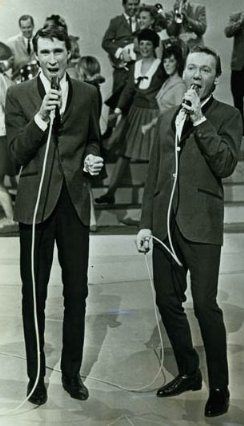

In the glittering, often deceptive world of 1960s pop music, a sound emerged that was so profoundly steeped in sorrow and desperation it stopped the world in its tracks. This was not just a song; it was an emotional typhoon captured on vinyl, a raw nerve exposed for all to hear. The masterminds behind this seismic cultural event were The Righteous Brothers, the duo of Bill Medley and Bobby Hatfield, who unleashed the timeless tale of heartbreak known as “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’.” Their genre, “blue-eyed soul,” barely described the sheer force of their performance, which brought the raw, unfiltered emotion of soul music crashing into the homes of mainstream America.

The story of the song’s creation is itself the stuff of legend, a moment of tragic alchemy. At the helm was the infamous producer Phil Spector, a man known for his towering ambition and revolutionary “Wall of Sound” production style. Spector didn’t just want a hit; he wanted to build a cathedral of sound, a sonic tapestry of sorrow that would feel larger than life. He enlisted an entire orchestra, layering strings, brass, and choirs to construct a grand, cinematic backdrop for the unfolding drama. This wasn’t just music production; it was the meticulous crafting of a weapon aimed directly at the heart. The result was a recording so dense and powerful, it felt as though the very studio walls were weeping.

At the core of this tragedy is the devastatingly simple, yet profound, lyricism. The song opens with a confession that has echoed through the decades, a statement of loss so intimate it feels whispered directly into your ear. A source close to the song’s emotional core revealed the devastating realization: “You never close your eyes anymore when I kiss your lips / And there’s no tenderness like before in your fingertips.” These words, delivered by Bill Medley in his deep, resonant baritone, set a scene of chilling emotional distance. It’s the sound of a love dying, not in a fiery explosion, but in a slow, agonizing fade.

The genius of the arrangement is in its relentless, soul-crushing build. It starts as a quiet murmur of pain, with Medley’s voice anchoring the sorrow. But as the song progresses, Spector’s Wall of Sound swells, the instruments and voices rising in a great wave of desperation. Then, in a moment of pure emotional release, Bobby Hatfield’s soaring tenor voice cuts through the chaos, a desperate, shrieking plea for reconciliation. The interplay is breathtaking—Medley’s grounded, aching pain against Hatfield’s sky-high anguish. It’s a dynamic that perfectly mirrors the internal battle of holding on while everything is slipping away. The song became a runaway #1 hit, but its legacy was cemented in its cultural endurance, most famously in a pivotal scene in the 1986 blockbuster Top Gun, which introduced the classic anthem of heartache to a whole new generation, proving that the pain it captures is truly timeless. The song’s final moments are a haunting cry into the void, a last, futile attempt to reclaim what has vanished: “Bring back that lovin’ feelin’, oh that lovin’ feelin’ / Bring back that lovin’ feelin’, ’cause it’s gone, gone, gone, and I can’t go on.”