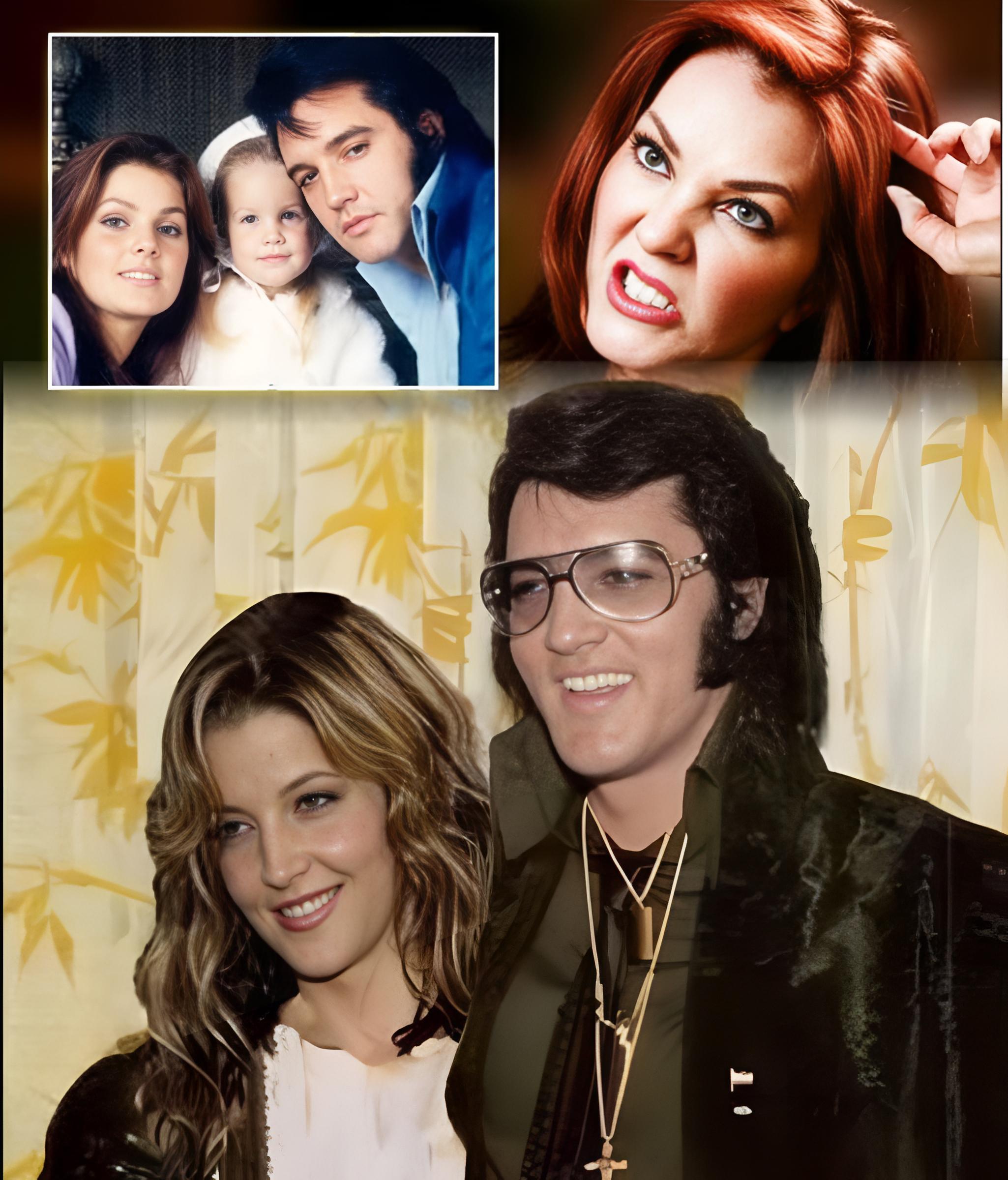

At 80, Priscilla Presley has stepped out of the long shadow of superstardom to offer a new portrait of the man the world called the King. Her account is intimate, unsettling and quietly human — a reminder that fame often hides the person beneath.

Priscilla Presley, Elvis’s former wife, speaks from a life lived at the edge of the spotlight. She says the public image of swagger and stage lights only showed a fragment of the man she loved. In a candid conversation, she described long nights at Graceland, private prayers at the piano and a man who sought comfort in gospel music and spiritual reading.

Priscilla, the woman who raised Elvis’s daughter and kept his private life from easy view, did not mince words when asked how the man she knew differed from the myth.

“He wasn’t who people thought he was,” Priscilla recently shared in an intimate conversation. “He was gentler. More vulnerable. And more burdened than anyone ever knew.”

Her image of Elvis is not of a hollow celebrity but of a restless soul. She says he felt isolated and exhausted by the demands of fans and the industry. Behind the jumpsuits and roaring crowds, she remembers a man who questioned whether anyone truly knew him, who read to find meaning, and who played gospel songs for solace rather than show.

That private portrait clashes with decades of rumor and tabloid shorthand. Priscilla, who lived with him and later guarded his memory, says some reports hit the mark but many missed the whole truth. The tabloids framed gaps and struggles as scandal; she frames them as a search for something deeper.

“He was brilliant,” Priscilla said. “But also tortured. He carried so much love, but so much pain too.”

Her words add texture to an icon who has loomed over generations. Elvis sold millions of records and shaped music for the ages. Those facts remain. But for older fans who remember his concerts and television appearances, Priscilla asks them to hold two images at once: the electrifying performer, and the private man who wrote notes to his child and wept quietly over gospel lyrics.

Priscilla’s account gives detail to familiar headlines. She confirms that Elvis struggled with identity and control. Yet she pushes back against two extremes — the worship of a flawless idol and the caricature of a man crushed by fame. Instead, she paints a figure who searched, who gave endlessly to music, and who kept a fragile interior life largely out of sight.

For communities of longtime fans, especially older readers who lived through Elvis’s rise, this reframing matters. It asks people to remember not only the music but the cost behind it. It places daily scenes — late nights at a piano in a Memphis mansion, prayer and reading — next to the spectacle of sold-out shows and glittering stage outfits.

Priscilla’s revelations have already stirred conversation among biographers, friends and fans. Some see new compassion in her telling. Others see confirmation of what whispers and hearsay long suggested. Either way, the story forces a reckoning with how fame reshapes the person at its center and how we, as a public, receive that person.

Priscilla ends her account with a plea to look beneath the rhinestones and the headlines. She asks fans to remember an imperfect, searching man who loved fiercely and hid his pain. And then, in a voice that has watched a myth grow and age, she leaves the image of Elvis suspended — not reduced to legend, not wholly explained, but somehow newly alive.